Our Philosophy

Sustainability

The term sustainability describes numerous, constant processes – sustainable developments. On the one hand, they ensure that our current needs get met. On the other hand, they guarantee that future generations will also meet their needs. For this purpose, the United Nations has formulated the “17 Sustainable Development Goals”. They are an urgent call to action because not a single goal has been met so far. Particularly complicated: All the resolutions are closely interlinked. Only if all are considered and advanced is sustainable development within reach.

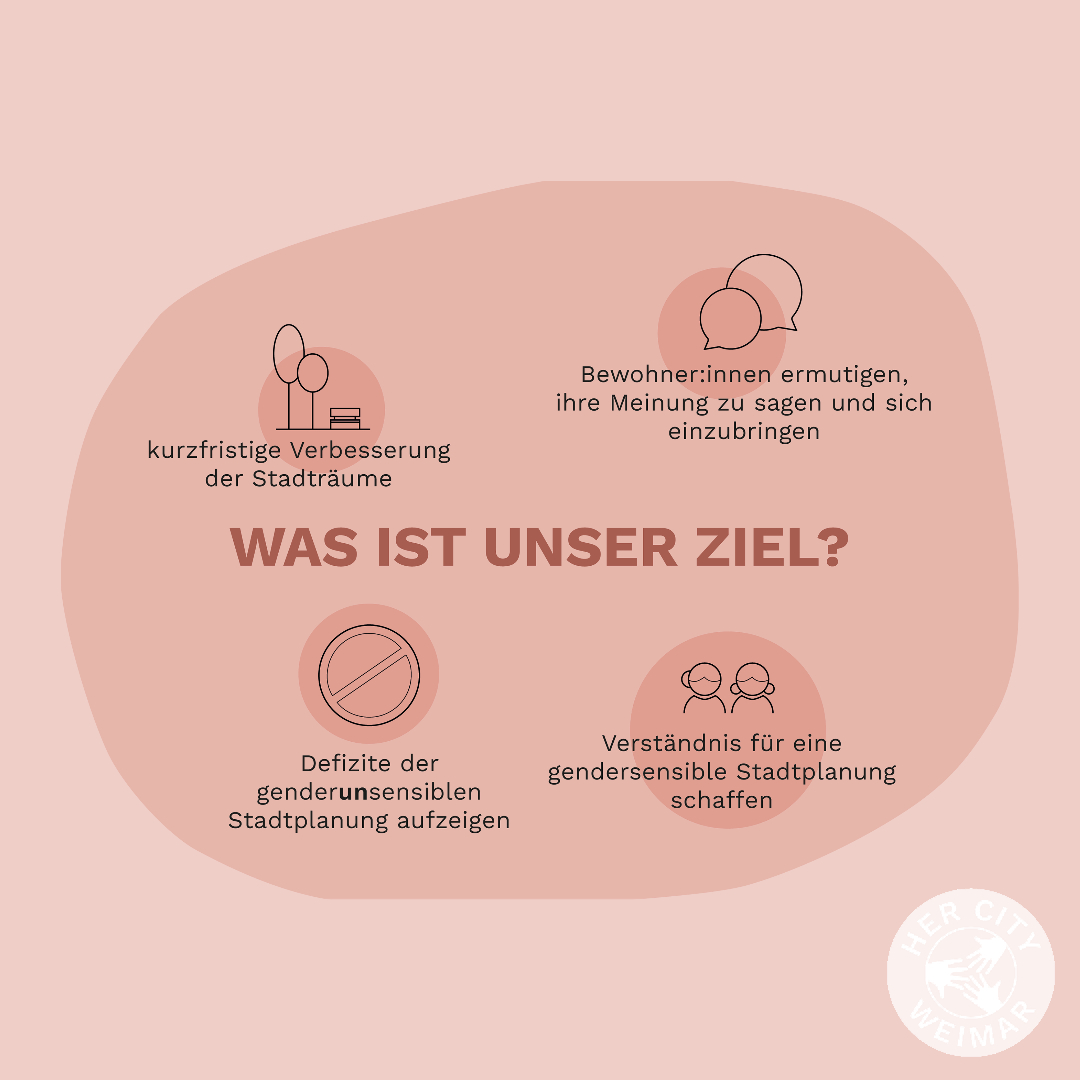

HerCity Weimar takes a closer look at the following goals:

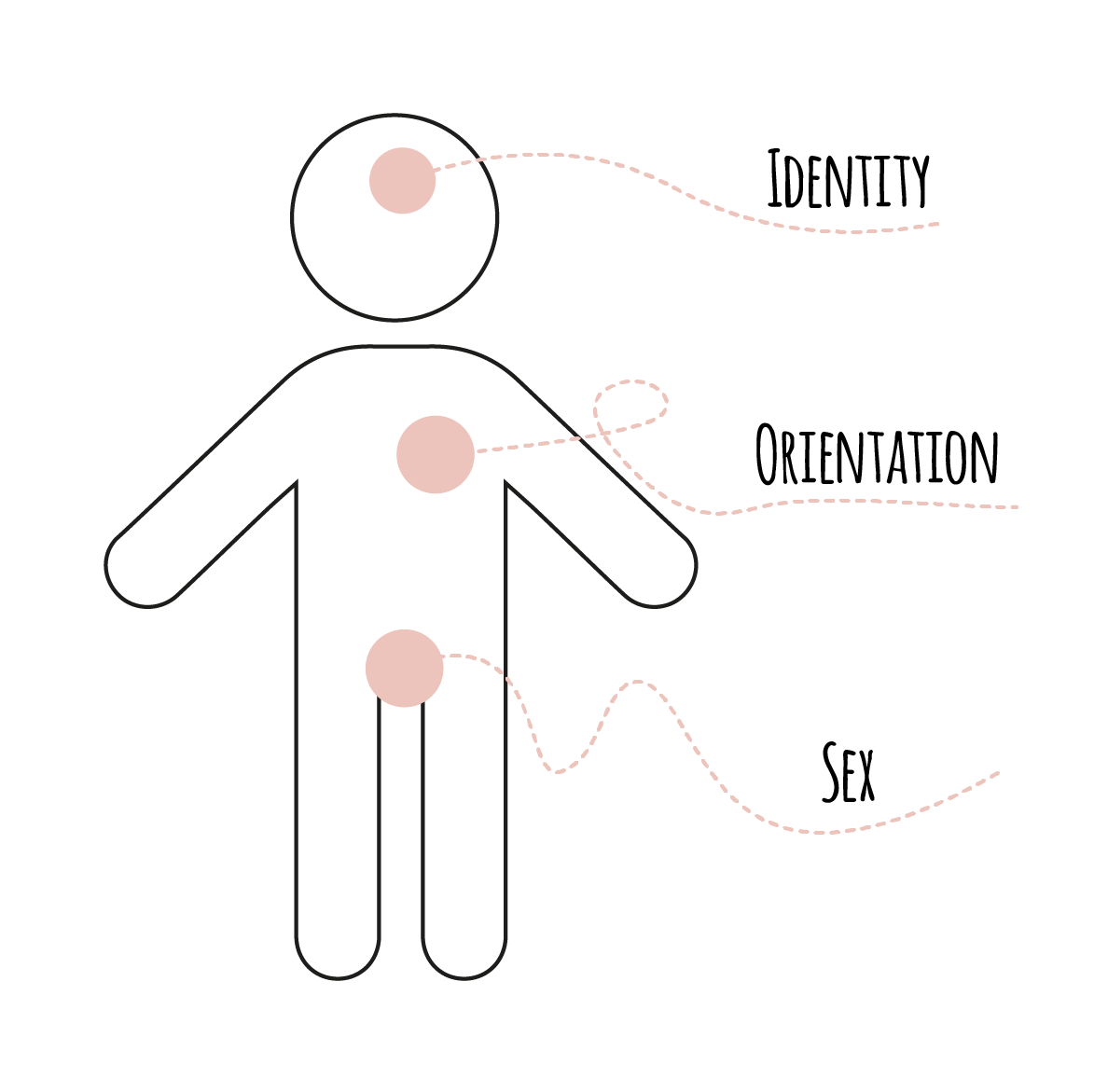

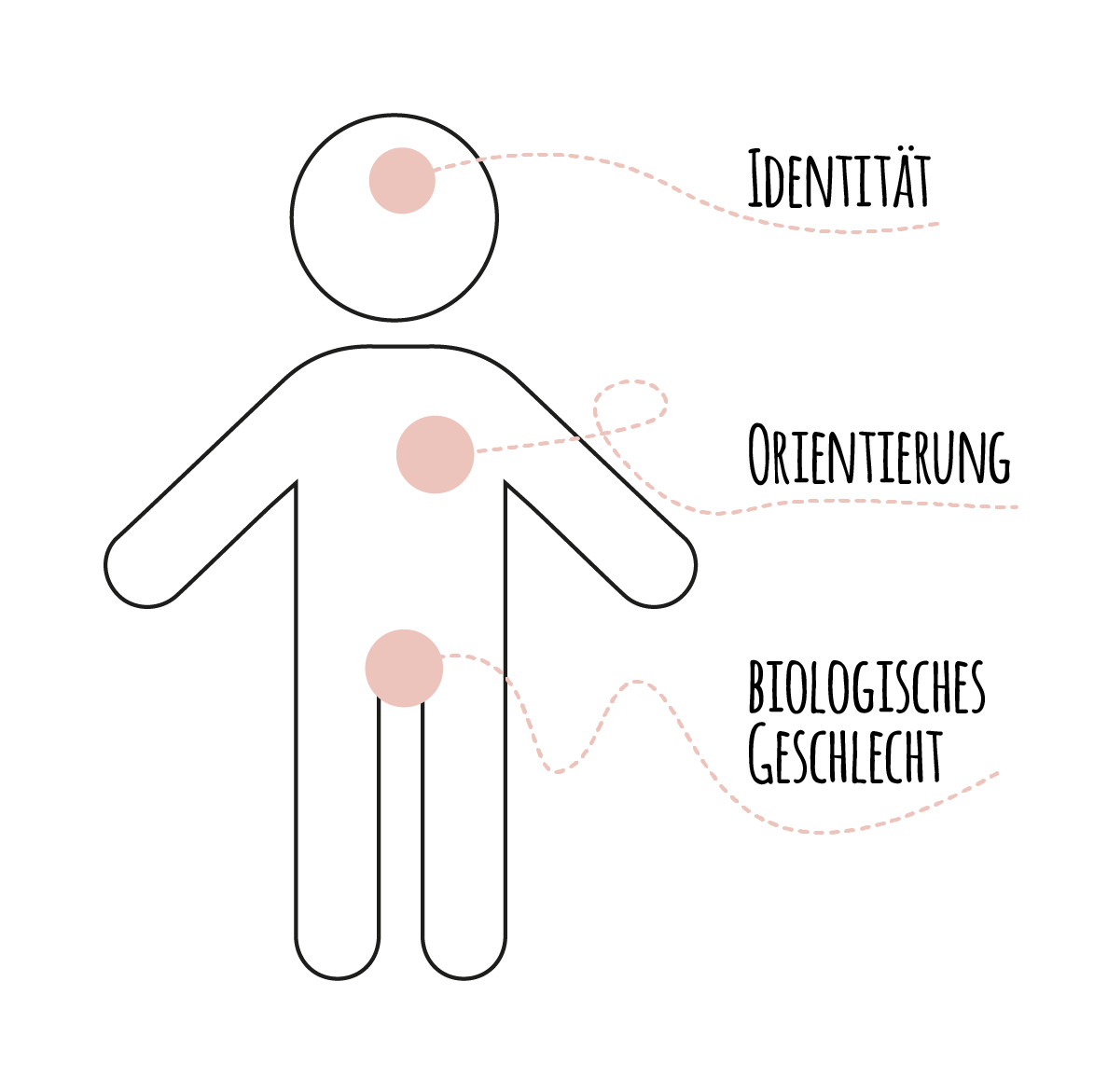

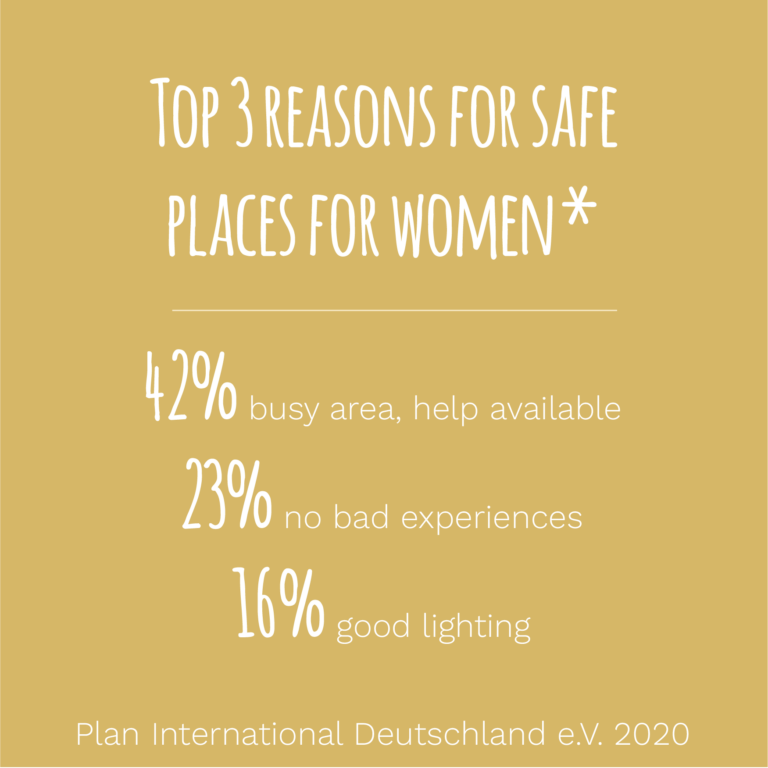

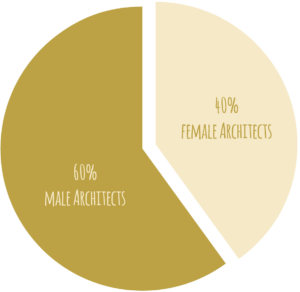

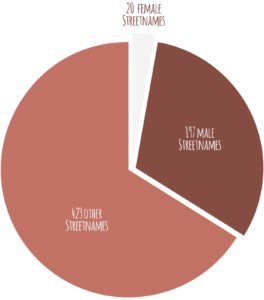

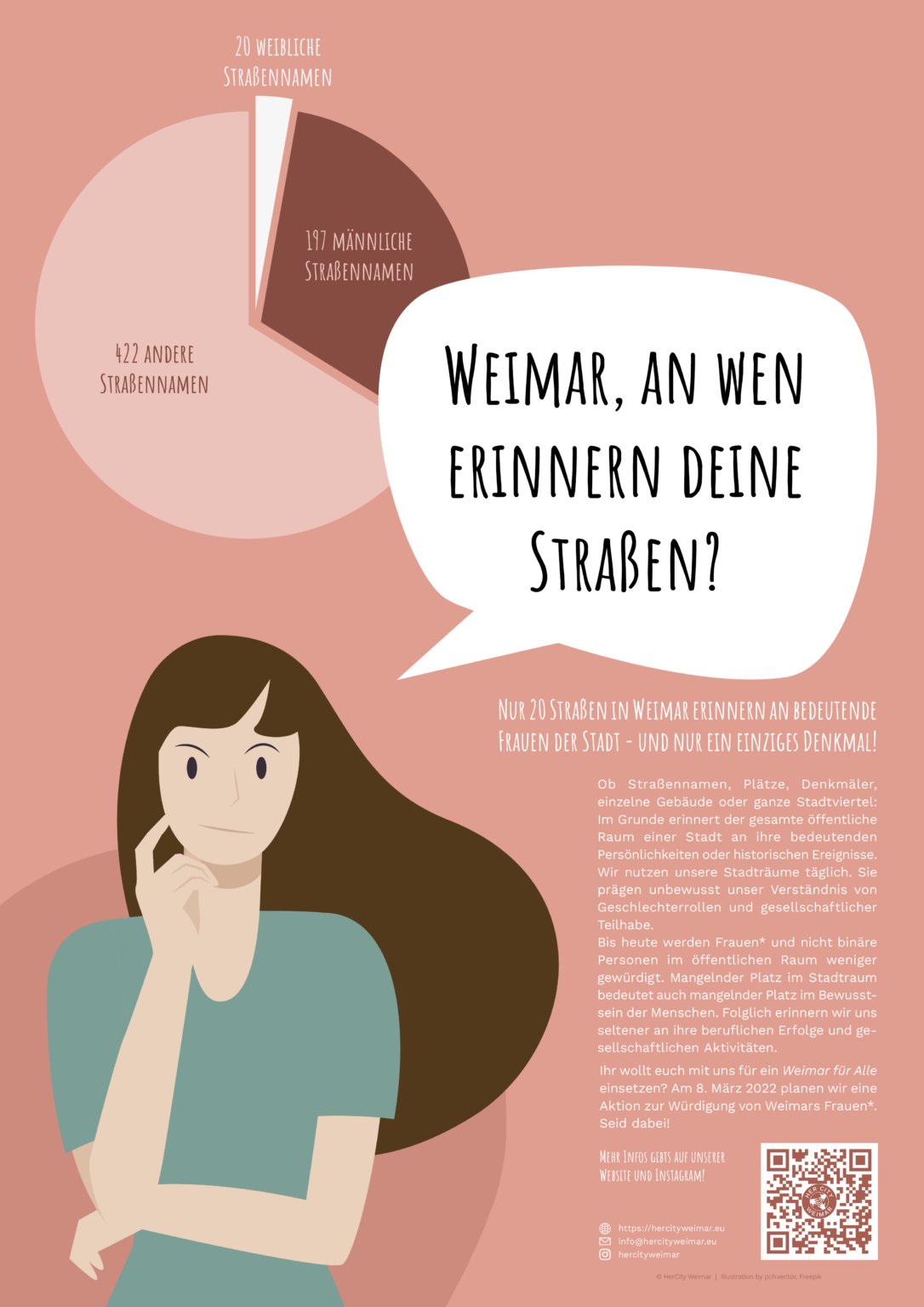

Goal #5 covers gender equality. It aims, in particular, to equalize opportunities and participation of women*, but also to fight against societal constraints and any violence against women*.

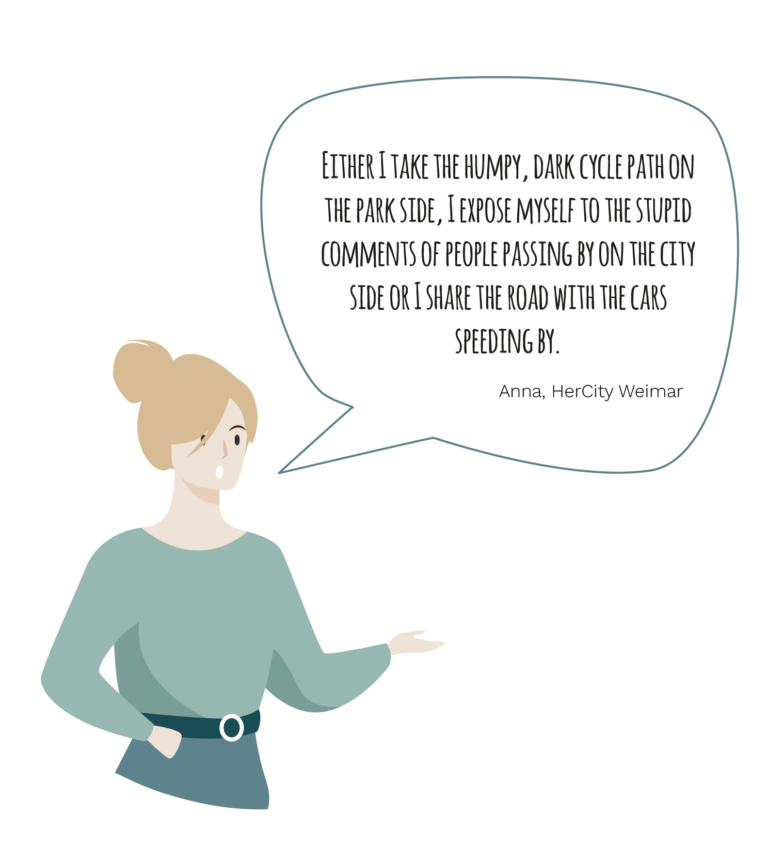

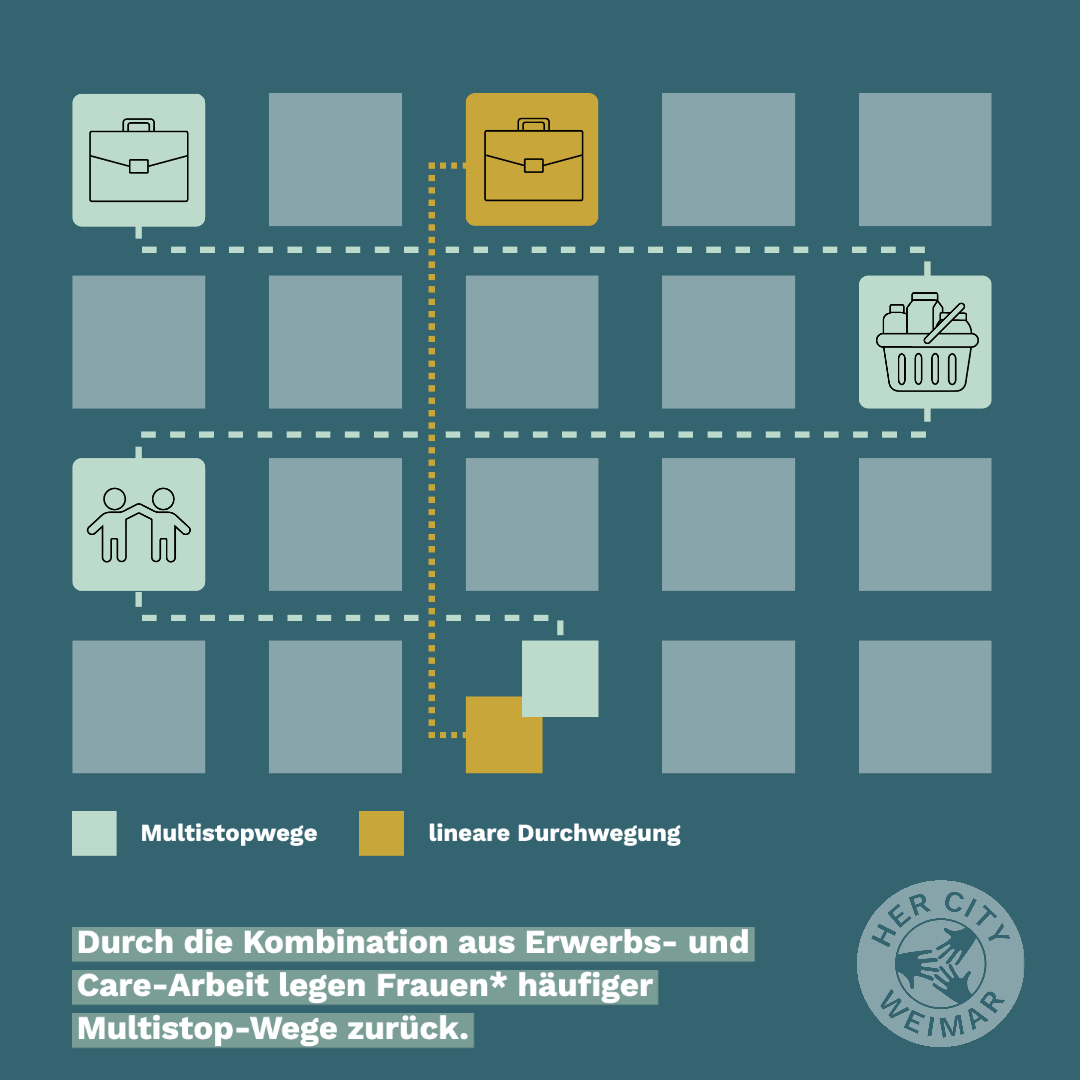

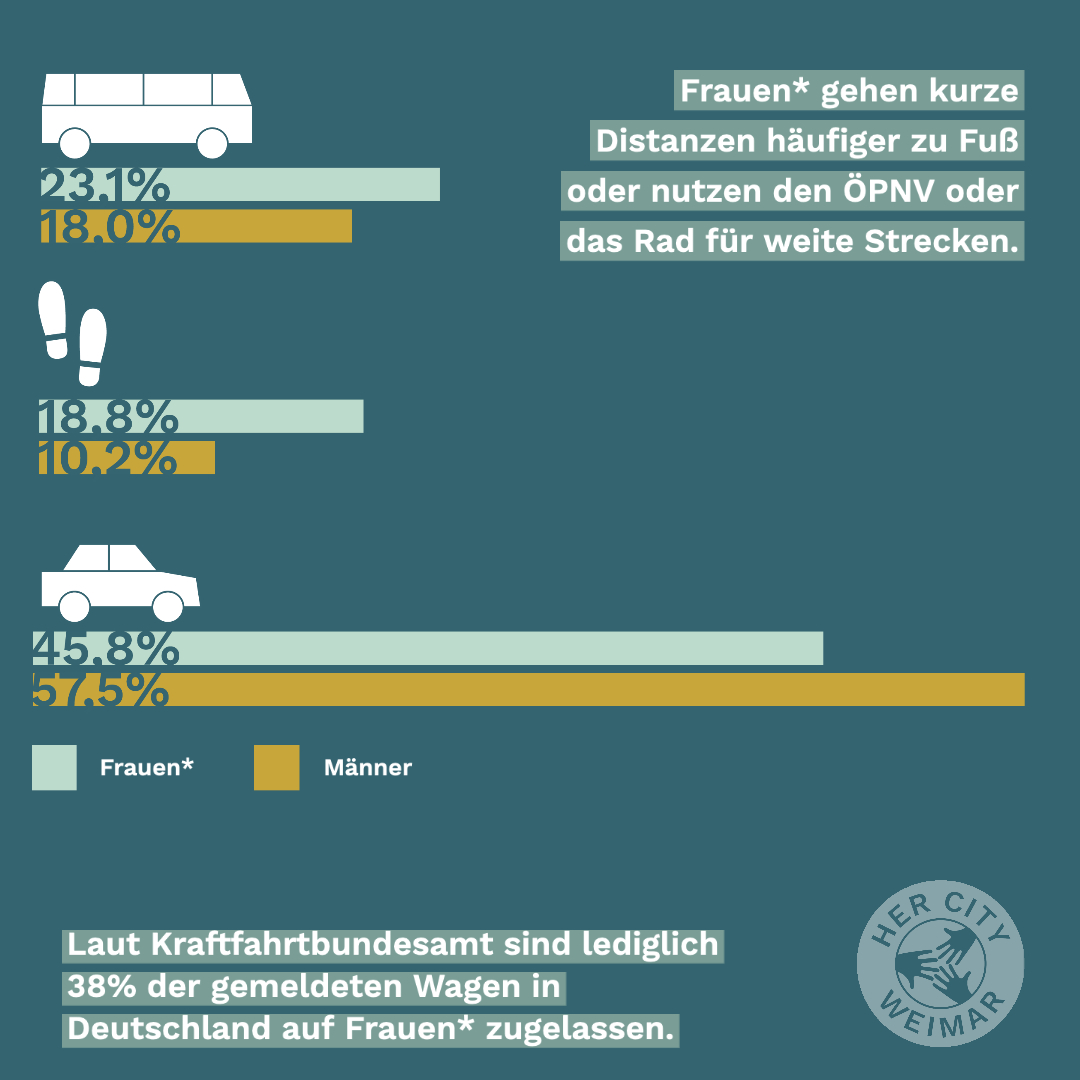

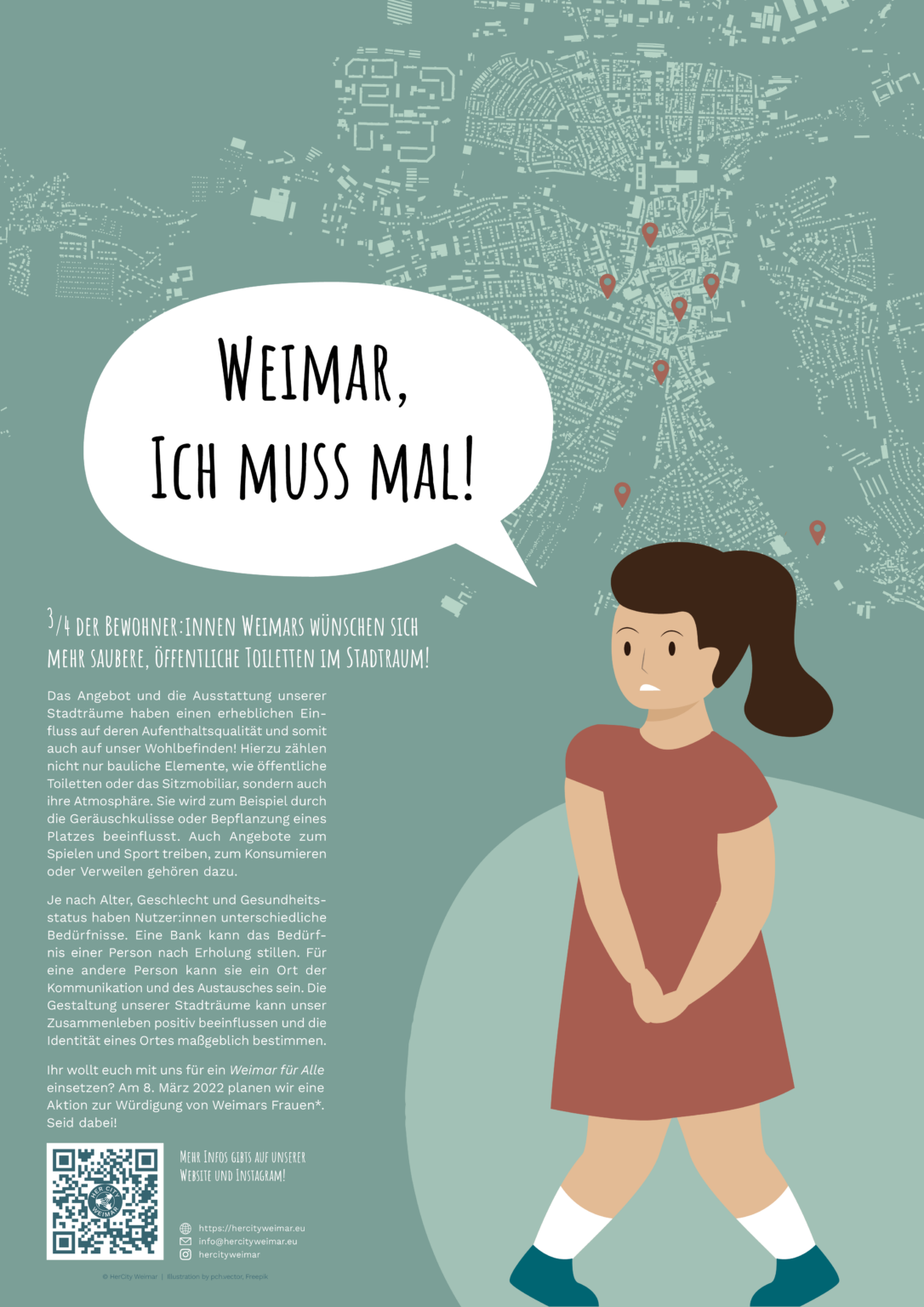

Goal #10 calls for the elimination of social, economic, and political inequalities. Instead, the equality of people should be strengthened and promoted, regardless of age, gender, limitations, origin, religion, or financial background. Public space cannot address this inequity on its own. Nevertheless, its design is essential to support everyday contexts, meet needs, and break down barriers.

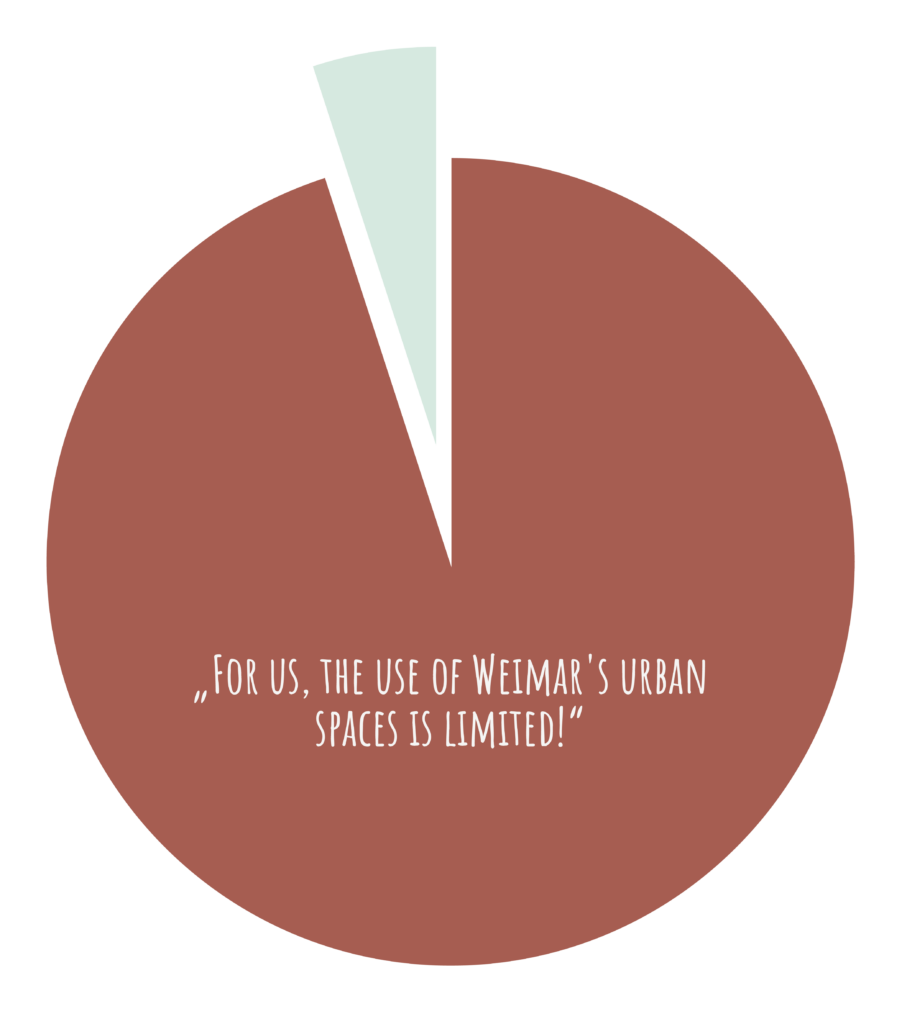

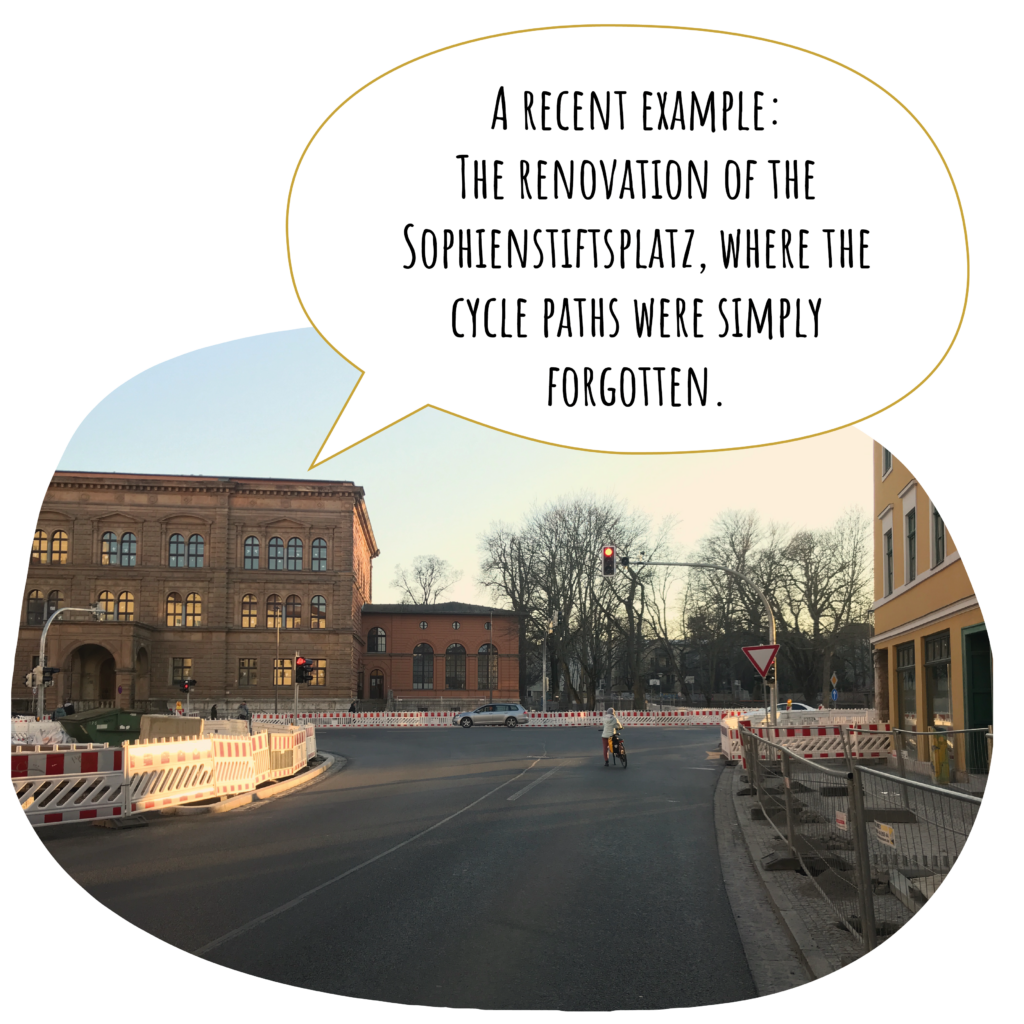

Goal #11 addresses the development of sustainable cities and communities. They should be made more inclusive, safe, and resilient. It also aims to guarantee that all people have universal access to public spaces and green areas in the future. That explicitly includes women*, children, non-binary and senior citizens, and people with disabilities. Their needs have been neglected in urban planning so far.

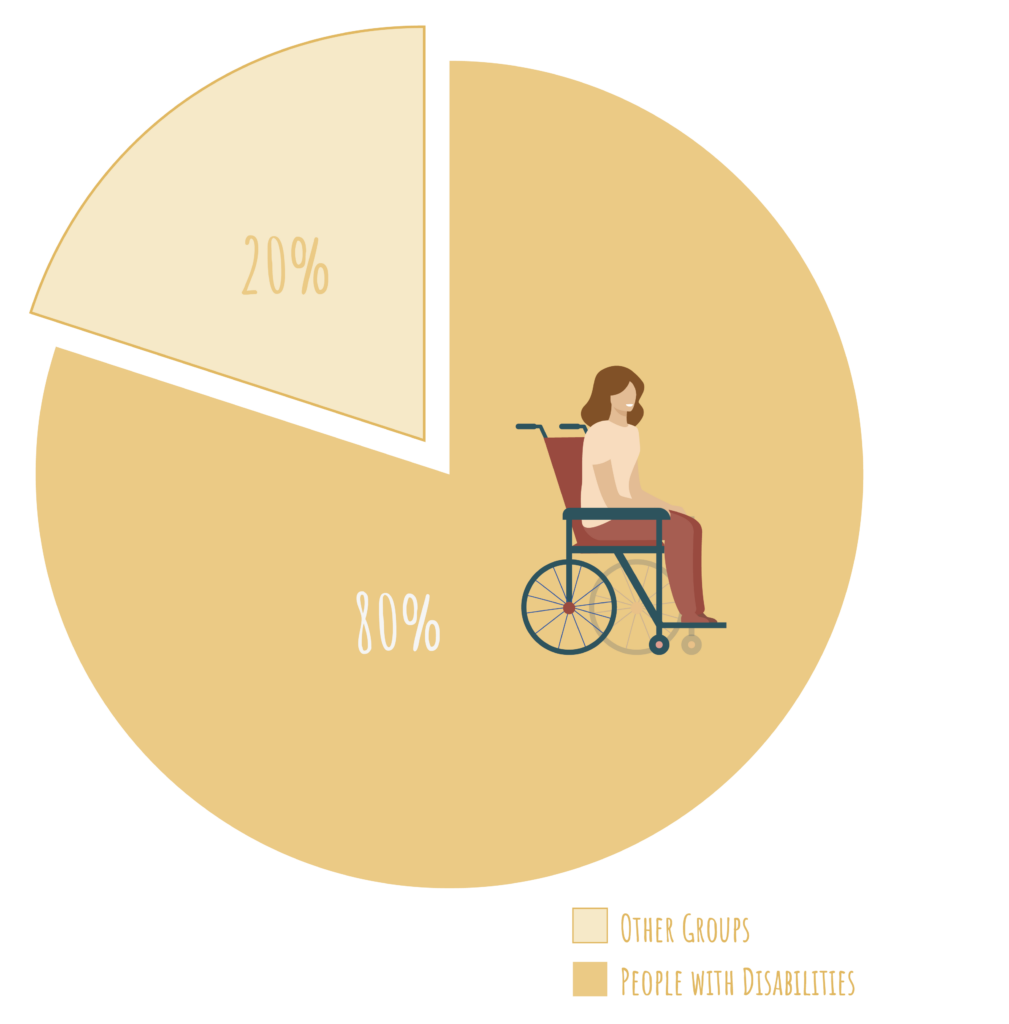

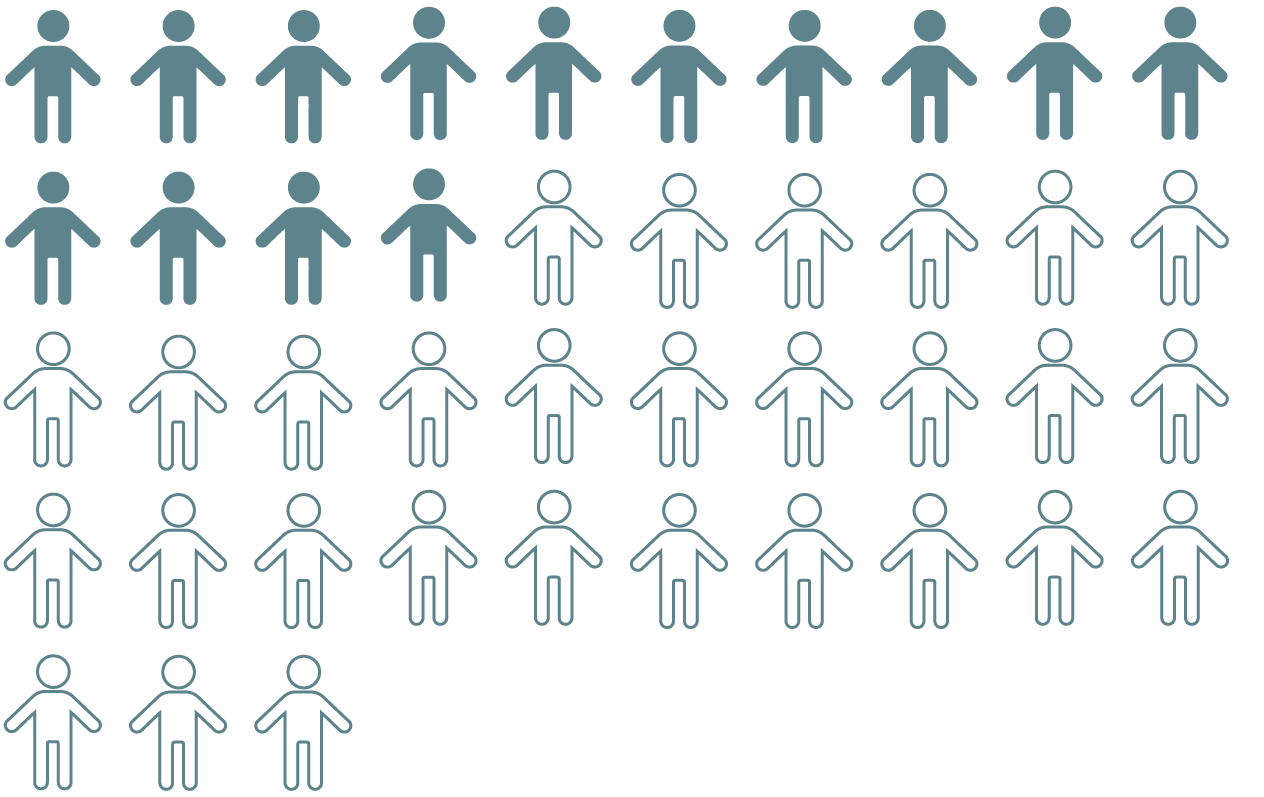

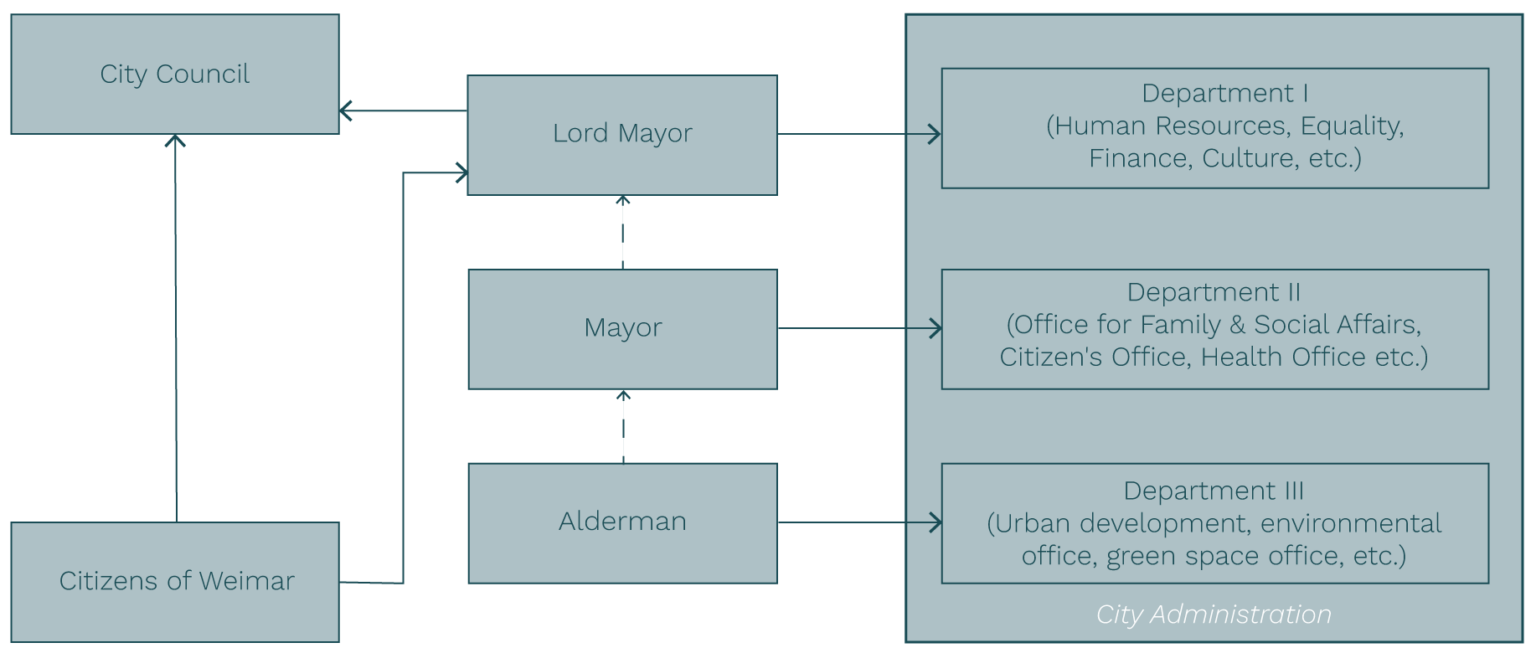

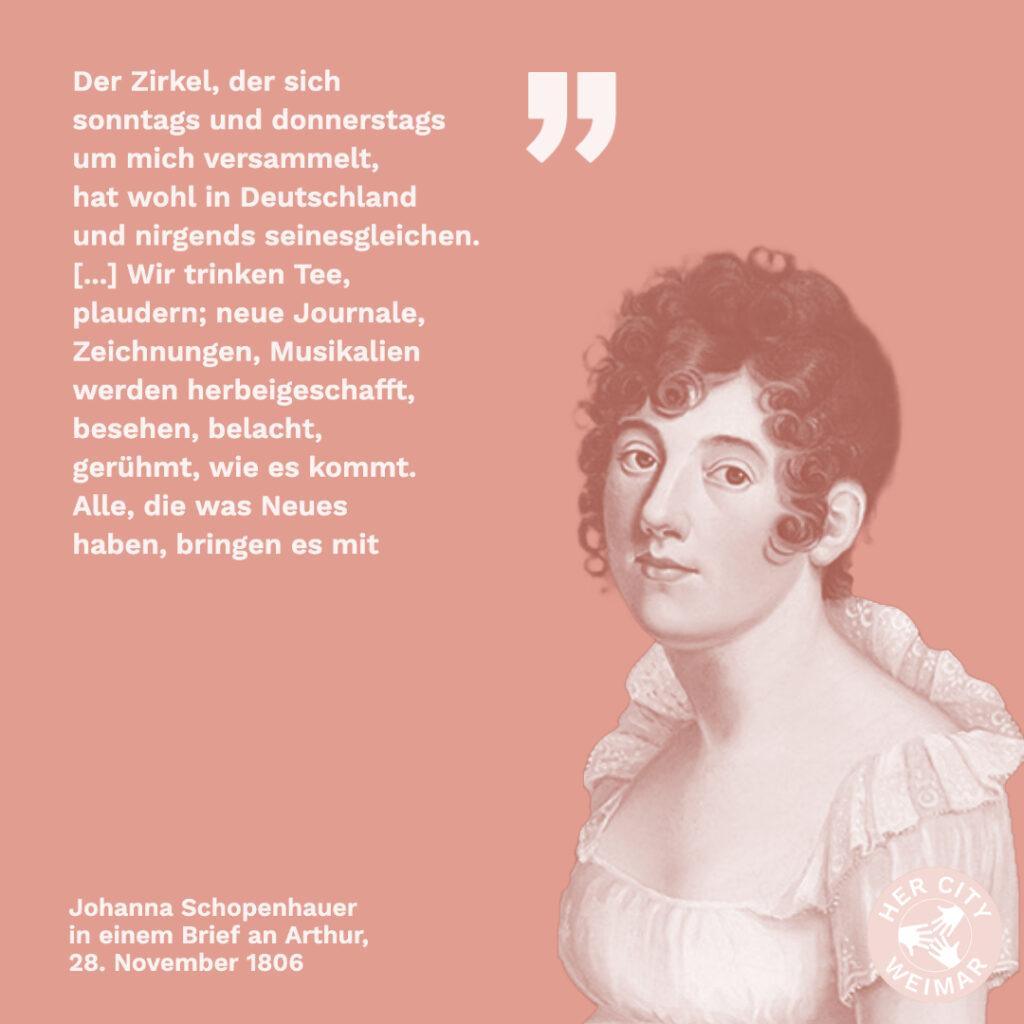

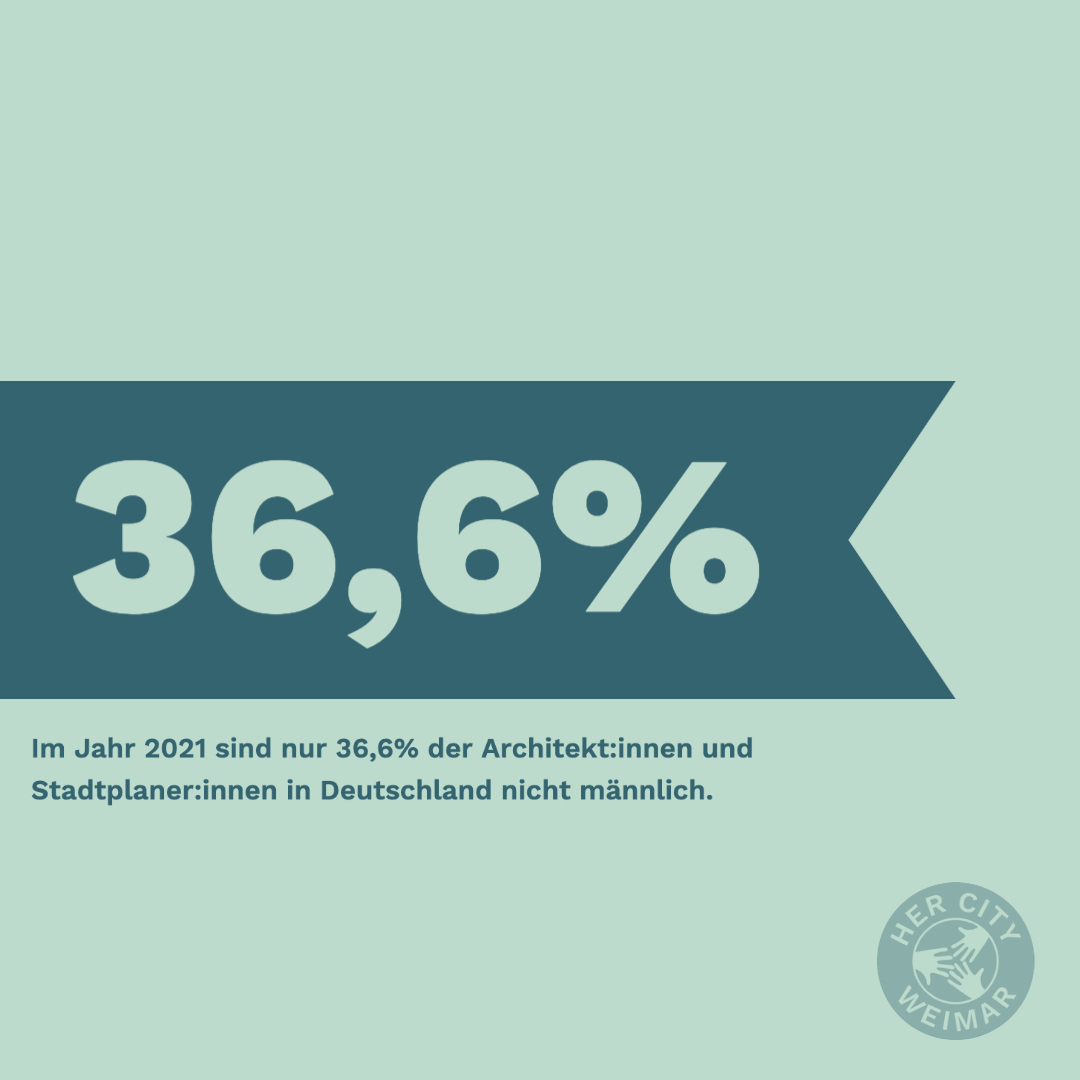

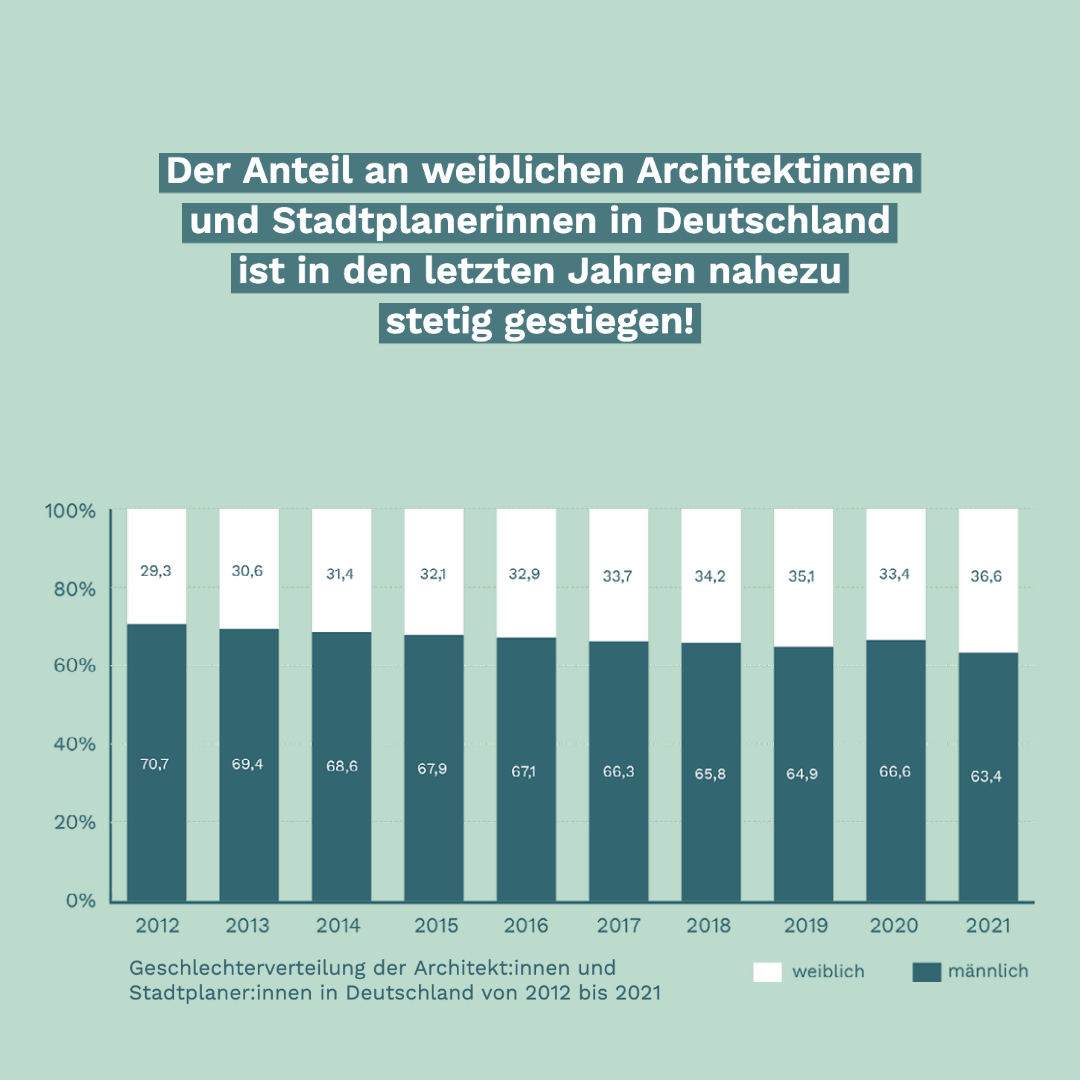

Goal #16 centers on, in part, cross-topic collaborations and politics. Responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making should be guaranteed at all levels. Those who have decision-making power also control the design of public space. Due to a lack of representation, the interests of children and young people, senior citizens, women*, and people with disabilities still play a subordinate role. They are supposedly the minority – but in fact, they are the majority!

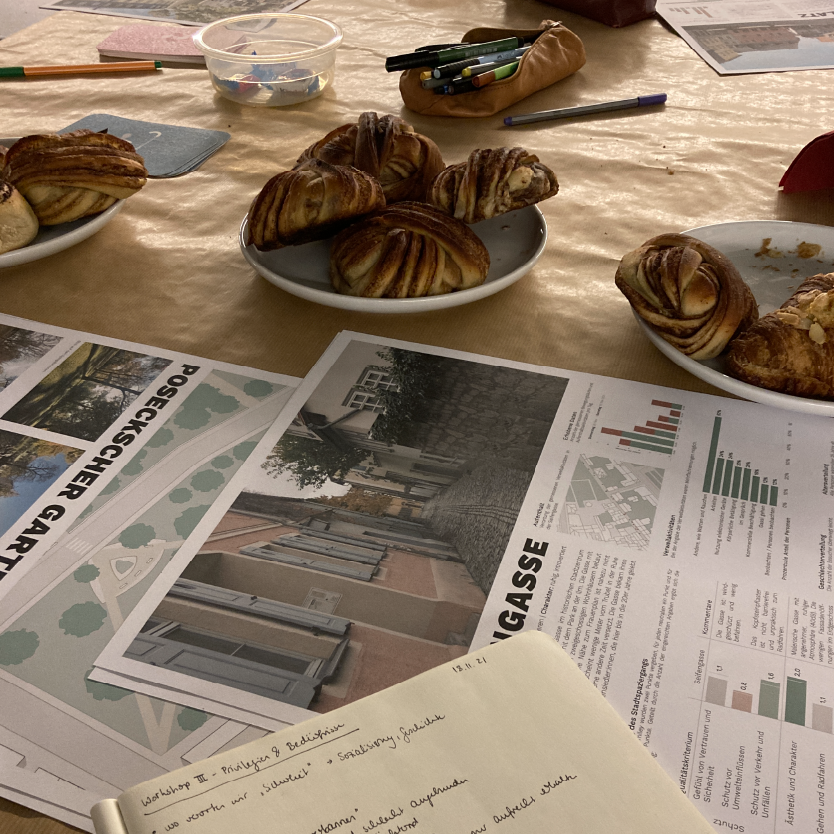

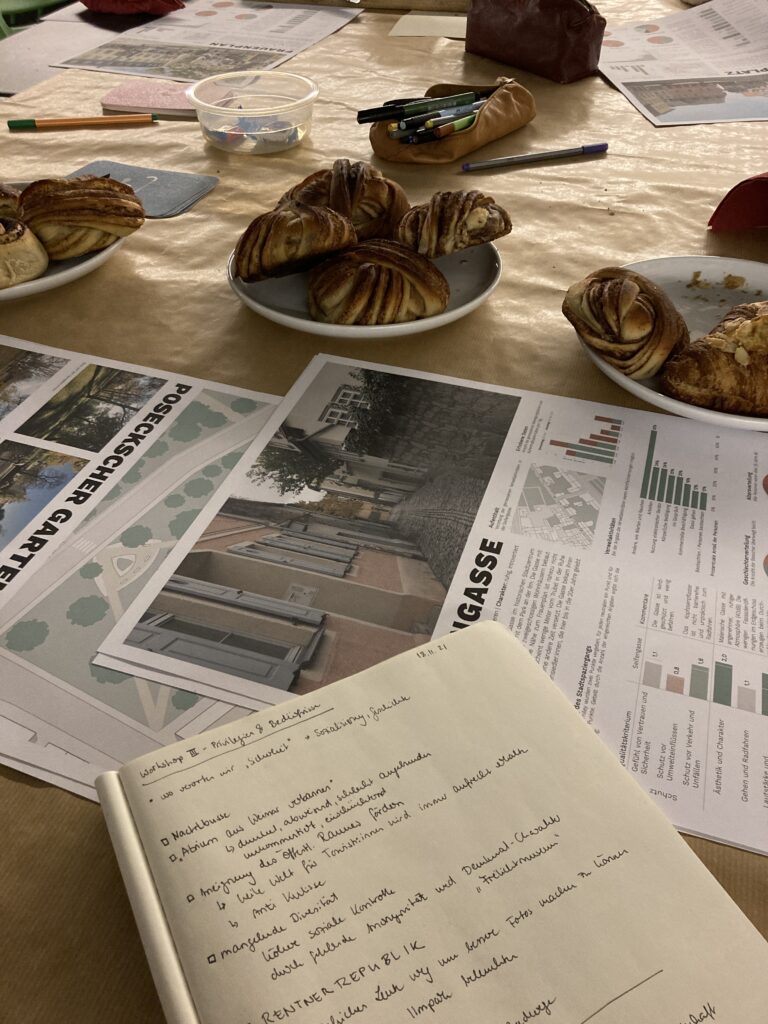

To implement all these goals successfully, we need to focus on our partnerships, according to Goal #17. HerCity Weimar has shown us that these collaborations exist not only on an international level but also on a local level. We can achieve more if everyone works together. That’s why we got in touch with numerous people, associations, and initiatives and built up a network. With open communication, we have raised the awareness for gender-sensitive urban planning and convinced people of our ideas.